Past Exhibitions

Resist with Love: The Xtopias of Solomon Enos Kūʻē me ke Aloha: Nā Xtopia a Solomon Enos

Kahu mālama ʻia na / Commissarié par / Curated by Skawennati

June 21 - August 18, 2024

Solomon Enos, Kū‘ē me ke aloha Resist with Love (2023)

Vast and Exuberant: The Futurist Imaginaries of Solomon Enos by Jason Lewis

“Aloha. My name is Solomon Enos. I am an artist, illustrator, and a game designer. And that's today. Tomorrow I might be a few other things. The day after that, I might be a few less things. [laughter] But very best way to put it is I'm a shape-shifter. In the most useful sense. [laughter]”

This is how Enos introduced himself in our 2017 interview. It still captures much of what I find provocative, entrancing, and joyous about his practice, a staggering volume of work across multiple media notable for its inventiveness, expansiveness, and generosity. He characterizes his practice as a conversation with his community in Hawai‘i that, among other things, seeks to create space to tell stories of the long past and even longer future of Kānaka Maoli. The works in Resist With Love: The Xtopias of Solomon Enos are but a small sample of his exuberant future imaginaries.

The exhibition features three works from Enos’ Akua AI series. ‘Akua’ is the ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi term that is often glossed (somewhat inadequately) as ‘god’ or ‘spirit’. In Hawaiian cosmology, the 40,000 akua have specific (if at times multitudinous) characteristics, roles, and spheres of activity. Whether making love, waging war, giving birth, or hunting for octopus, there is an akua who is responsible for—and responsive to—those activities.

Enos describes the Akua AI as experiments in “magical realism as ancient deities begin to upload themselves into digital realms to challenge the new gods of misinformation and greed.” These deities first come into being as Kānaka Maoli knowledge-keepers and scholars began digitizing the vast trove of Hawaiian-language newspapers published from 1834 to 1948. As the texts became part of cyberspace, the Hawaiian akua which they describe took shape in virtual space, adapting to its computational fabric. They develop Artificial Intelligence avatars who accompany Kānaka Maoli as they extend Hawaiian knowledge practices into this new territory.

Enos is a great lover of science fiction, and the Akua AI were inspired by William Gibson’s Sprawl Trilogy and Neil Gaiman’s American Gods. Gibson coined the term ‘cyberspace’ in the first Sprawl novel, Neuromancer (1984). In the second, Count Zero (1986), he imagined a globe-spanning AI emerging out of cyberspace in the form of avatars modeled on the loa (spirits) of the Haitian Vodou tradition. The AI chooses these avatars to facilitate communication with its human creators across profound differences in cognitive apparatuses.

Enos draws on Gaiman to imagine how new gods come into being, old gods pass, and gods new and old migrate from one territory to another. In the novel American Gods (2001), Gaiman considers how gods require believers to exist, and thus their power waxes and wanes as the number of those believers—and the degree of their fervor—grows and diminishes. He imagines new gods spawning alongside new belief systems, such as those driving fantasies of American industrial-techno-media exceptionalism, as they come into being.

Enos’ Akua AI are old gods moving into new territory. Kāne is the akua of fresh water and light, and his AI avatar uses his ʻōʻō (pick-staff for finding water) to dig into the soil—the substrate—of cyberspace, bringing forth vitality and abundance to counter the rot instigated by the selfish techno-solutionism of Silicon Valley. Hina is the goddess of the moon, maternity, and making kapa (bark clothing), using her i‘e kuku (a grooved club for beating tough plant fibers smooth). The Hina AI’s i‘e kuku has 0s and 1s rather than grooves, and she uses it to beat the fabric of cyberspace to “rework the tapestry of the human story by disrupting the global and local communication networks of right-wing extremists, white supremacists, and all the forms that authoritarian dictators and demagogues take.” And, finally, Mo‘oinanea is the mother of all the mo‘o, the lizards who guard fresh water; mo‘o are also the storytellers. In cyberspace, data is the water that nourishes everything, and so the Mo‘oinanea AI tends to the quality of the information flowing through virtual spaces, fighting against misinformation and misuse of peoples’ personal data, while ensuring traditional mo‘olelo find their place in this new world and fresh mo‘olelo are created to respond to evolving realities.

Enos is opening discussions with his community about the great challenges of our time—like AI—in a Hawai‘i-rooted way. He hopes the Akua AI series will also inspire other Indigenous communities to bring their akua, or their ways of making sense of the world, into these new virtual-digital-computational territories. As he notes, “at times it seems our species knows more about building rockets than we know about what it means to be human”. At this moment, in 2024, we know much about building machines for extraction and exploitation. Perhaps Enos’ Akua AI can show us how to create them otherwise, such that we better know ourselves as we venture ever further into an ever-deepening ocean of bits.

[laughter]

Cheyenne Rain Le Grande ᑭᒥᐘᐣ

Mullyanne ᓃᒥᐦᐃᑐᐤ

April 27- June 8, 2024

Mullyanne by Becca Taylor

Mullyanne, The movements of your ribbons reminds me of the setting sunset along the lake. How the pastel colours ripple into one another as the calm waters dance reflecting the sky back to itself. Growing up visiting a Northern Alberta lake not so different from your own, I can feel the calm coolness radiating from the waters’ edge as the sun gently begins its decent to rest behind the horizon. Whenever I leave the prairies, I yearn for the sky. Which is probably why I never leave long.

Mullyanne, The flattened pastel light, soft movement and tenderness ebbs me in between two-states. Like the littoral of a lake shifting between reality and an alternative state. A dream state. I spend time immersed into your reality but shift back into my own body as a witness. Different realities come together to make up a community, a story, an understanding. Right now, I am listening and witnessing to yours. Learning as I watch you shift in and out of space.

Mullyanne, The beads that are adorned to your face reminds me of words of Métis Scholar Sherry Farrell Racette. She shares that “Language, symbolism, and continuity of practice 'grandmothered' ancient meanings on to new forms; rather than marking a decline in material culture, they illustrate the important work of women in the creation and synthesis of knowledge systems”[1] While she focused on beads, fibres and cloth in her investigations. I see the continuation of continuity of practice in the Bepsi tabs and the platforms of the moccasins. How language and your cultural understandings are embedded into the construction of the garments. A showcase of fluidity, survival and adaptation of cultural understandings and knowledge transfer. How each item is unique to you but taught by our ancestors.

Mullyanne, the futurity of your materials reminds me of the words surrounding the concept of Indigenous futurisms[2] of mixed Anishinaabe and settler author Grace Dillon and Métis writer Chelsea Vowel. Dillion points out that Indigenous futurisms is ‘how personally one is affected by colonization, discarding the emotional and psychological baggage carried from its impact, and recovering ancestral traditions in order to adapt in our post–Native Apocalypse world.” Chelsea Vowel states: “Indigenous futurisms are not merely synonymous with science fiction and fantasy, despite how they may be viewed as such within the mainstream. Indigenous futurists express their ontologies in various forms, and as Grace Dillon puts it, “our ideas of body, mind, and spirit are true stories, not forms of fantasy.”[3]

Mullyanne, I am surrounded by Language. Syllabics on the wall. The soft echo of your voice singing an identifiable song, that I understand even though I do not know the nēhiyawēwin words to sing with you. It’s enchanting and comforting. You share with me crystal visions. Unlike Stevie Nicks you do not keep these visions to yourself but share them with us. A future centred in Nehiyaw Isko knowledge systems, language and the prairie skies.

[1] Sherry Farrell Racette, “My Grandmothers Loved to Trade: The Indigenization of European Trade Goods in Historic and Contemporary Canada,” Journal of Museum Ethnography, No. 20 (March 2008): 77

[2] The term Indigenous Futurisms was first used by Grace Dillon in 2003. Indigenous Futurisms was used to describe a movement within art and media forms that expressed Indigenous perspectives on future, present and past.

[3] Chelsea Vowel, “Writing Toward a Definition of Indigenous Futurism,” Literary Hub. June 2022 https://lithub.com/writing-toward-a-definition-of-indigenous-futurism/

Cedar-Eve

Mnidoo Gamii

April 27- June 8, 2024

Cedar Eve : Mnidoo Gammi

by Chalsley Taylor

Energy never dies — it can only be transformed. There are multiple realms of existence and, in death, our spirit only passes into another such realm. Mnidoo Gammi, Cedar Eve’s first solo exhibition, affirms connections that sustain across myriad boundaries; in it, we encounter both those present in our physical plane and those who have transitioned beyond it.

Cedar’s mother lives in Toronto, where the artist grew up, but is from Saugeen First Nation. Her father’s side is from Wikwemikong Unceded Territory. In this way, Mnidoo Gammi (so-called Georgian Bay), forms a locus of the artist’s lineage. Her mother’s land rests on Lake Huron, along the Bruce Peninsula; Mnidoo Gammi is the body of water that connects this Peninsula at Manitoulin island, where Wikwemikong lies. Anishinaabemowin for “Spirit Lake”, this water speaks to interrelational dynamics that echo throughout the exhibition, situating the conversations generated between its pieces. We witness Cedar’s formal strategies build upon one another across mediums to reflect gestures of care, interconnection and play. Within her distinct visual language, few if any discreet bounds exist between entities we observe, human or otherwise; spirits depicted in vibrant, abstracted forms flow into one another.

Cedar identifies community as a central part of her practice, noting this was lacking in her early years.[1] In her pieces, expansive spiritual entities often fit themselves into the spaces around or between photographed subjects, their limbs curved to hold friends, family or Cedar herself. Their presence appears protective or comforting; at times, their heads tilt inward to rest against those of loved ones.[2] Spirit Stitch, cotton pillows featuring portraits of Cedar’s parents, draws together family and restorative care. An offering to the artist’s dream world, the collection oscillates between the physical and metaphysical. With a history of intense and vivid dreams, the artist notes she sometimes awakens feeling as if she’d not rested at all. It was a common occurrence for her and her brother, Zach (ba), to have similar dreams in the same night despite living far apart.

The link between the physical and metaphysical is reprised in Honouring the Dead, a series depicting loved ones “called to continue their spirit journey”.[3] Creating these works provides a constructive method for the artist to process her grief, for it is an act of reflection and communion with the deceased. Cedar is in dialogue with these individuals as she adorns their photograph amidst a torrent of memories, such that the completed works stand as mnemonic devices, surreptitiously stirring up stories painful and humorous alike. Yet, as she notes, Honouring is not intended to centre the trauma of loss, citing her purposeful use of bright colours to produce intricate beauty. As in Spirit Stitch, Honouringdelineates Cedar’s lineage from her point of view; concretized in these works, this lineage elides the division between blood relations and chosen family. In this archival series, which curator Cécilia Bracmort describes as “a visual altar,” the artist combines beading and photography — both of which techniques, as Bracmort notes, “are related to the notion of time: an elongated time for the former and the instant (snapshot) for the latter”.[4]

Works in Mnidoo Gammi conspicuously mark time even as they collapse it. Cedar often appropriates archival practices to her own ends, best reflected in Cedrus Annum, a series of daily self portraits. Here we are charged to consider the ways in which these practices refuse prescriptions of historic archival sciences and undermine their authority. With the artist controlling what can and cannot be discerned, how should we (how can we) impose any organizational structures beyond the chronological? How are the various parts to be categorized, named and thus defined? To some extent, Cedrus Annum also functions as a personal history, one whose primary modality is play. The artist frustrates our attempts to decipher the moments (and selves) recorded in these images: Drawing over the instant photographs to control our view, she adds faces or blocks of colour to some; elsewhere, small markings appear in decorative motifs. Other portraits appear without any modification at all.

As Cedar Eve illuminates, obscures and transforms at will, her work insists upon the indelible nature of the relationships connecting the artist to her community, family, and past selves. Though the works we encounter in Mnidoo Gammi are deeply personal, she extrapolates the intimate into singular visions of interrelational connection, communication and self-representation. Post encounter, we may begin to perceive the mutability of time for ourselves.

[1] Usher, Camille. Relations, 2016, 36–41.

[2] Depicted in Cedar Eve, “Nokomis/Zigos (Grandma/Auntie)” from “Honouring the Dead,” 2012.

[3] Michael “Cy” Cywink, Personal communication to Cedar Eve, March 2024.

[4] Cécilia Bracmort, Personal communication to Cedar Eve, April 2024.

Greg Staats: nahò:ten sa’tkahton tsi niioháhes? / qu’est-ce

que vous avez vu en chemin? / what have you seen along the way?

curated by Hannah Claus

February 3 - April 6, 2024

What have you seen along the way?

Curatorial essay by Hannah Claus

This question resonates with me throughout my conversations with Greg Staats. It is the question posed by the Peacemaker to Aionwatha: we need to share all that we bring with us, so that we may add these ideas and extend the rafters of the figurative longhouse that is the Rotinonshonni Confederacy.

Our responsibility as Rotinonshonni lies in keeping balance through rendering order to chaos. One of the ways this can be seen is through the recitation of the Ohénton Karihwatéhkwen [The Words Before All Else], in which we greet, name and acknowledge all that is around us. We begin within ourselves and extend outward to the Lower, Middle and Upper Worlds. When speaking these words, we recognize the relationships that connect us to all of creation. The process of this recitation brings us closer to a good mind and being a part of the Great Law of Peace.

The complication in trying to walk this path is that we live in a post-contact colonial world. The Peacemaker has given us our instructions, but language, communication, ways of being and doing, have broken down. In this constant state of disruption, we continuously adjust our positionality to negotiate colonial reality. Do’-gah - I don’t know [shrugging shoulders] speaks to this state of liminality: caught between footsteps we are rendered language-less, expressing our non-engagement through a shrug, in this way building up a reflexive layer of protection through repetition and time.

Do’-gah - I don’t know [shrugging shoulders] is placed on the outer wall before you enter the gallery space. At The Edge of the Woods, if you will. This is to underscore the sacred sense of safety of an emotional architecture that is the gallery. As when under the rafters of the longhouse, here we may gather to collectively express, listen and share.

A good mind is non-judgemental: it accepts, observes, listens. For Staats, this is his work as an artist. His images are intuitive mnemonics that take the place of his missing language. The series 1969 names chaos as a resonant echo, regrouping the local and familiar with larger external forces: from black mold staining a ceiling; to the cover of The White Paper,[1] and even greater, an image from Altamont.[2] Staats appropriates this image by photographer Beth Bagby through an addition of a mnemonic[3] to its surface, in this way reuniting the female [gaze] and male [responsibility]. These stand as evidence of chaos and protest with other visual signposts included to provide balance and forward movement: sumac, pine, ashes… – signifiers of healing, protection and encouragement.

The Peacemaker said, “All who wish to join the Great Peace may follow the roots of the Great White Pine.”

The white pine was chosen as a symbol of the Confederacy as it was the largest, strongest tree. Everlasting. An eagle sits at its top to watch and call out. We are that tree. With a clear mind, we have that vision of eagle. Yet behaviour resulting from chaos gets in our way. In Untitled [white pine roots] we see a close-up of the ground crowded with roots peeking through its surface. These are both the white roots of peace, an invitation, but also silent indicators. As Rotinonshonni, we hold “the faces yet to come” foremost in our actions. However, we must acknowledge this earth also tragically holds the ancestors who never were. We need that strong voice of Eagle.

In the journey back to the longhouse, the goal is to “cross the threshold”. The wampum installation, Untitled [renewal portal], expresses this penultimate destination. White is Truth. It is an invitation to live under the Great Law of Peace, to live with compassion. As a portal to the hold of community, this installation represents a constant embrace, as well as the desire of potential. The decision to take that step, to cross the threshold, is yours.

This is our journey. This work we are doing with integrity, responsibility and autonomy, is both for ourselves and for community. For Staats, “crossing the threshold” is the endgame. Within the longhouse, we bring with us all that we carry now in this time of post-contact and dispersion. Our triumphs and mistakes all have meaning. And as we keep adding to the rafters, the collective continuum that is the Good Mind and the Great Peace, continues to grow.

Skén:nen.

[1] https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/the-white-paper-1969

[2] https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/lifestyle/altamont-rolling-stones-50th-anniversary/

[3] The symbol represents one of the fifty [male] Haudenosaunee titleholders, Tiohnekwen, of the Wolf Clan.

Nahò:ten Satkáthon tsi Niioháhes?

By Hannah Claus

Kí nahò:ten kari’wanóntha wakonnién:ni thénon akatkátho tsi nikarí:wes teionkení:thare ne Greg Staats. Ne ni’ óni rori’wanontón:ni Ayenwátha ne Skén:nen Rón:nis: kari’wanóntha sha’taetewátste nahò:ten ientewá:hawe, oh naiá:wen’ne iaetewahsón:teren tsi kanénhstahere ne kwah tokén:en ahontkátho ne kanonhséhsne, né:ne Haudenosaunee Raotitióhkwa.

Tsi nahò:ten ionkwaterihwaién:ni ne Haudenosaunee né ki’ ne sha’taióksteke tsi aietión:ni ne taonni’tón:ni. Énska tsi nakaié:ren ne aiontkátho né:ne aiaié:ron ne Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen (The Words Before All Else), e’tho tentewatenonhwerá:ton eniethina’tón:nion naho’ténshon teionkwahkwatasé:ton. Í:i entitewatatié:renhte thóne ientewatahsón:teren Ehtà:ke, Ahsennónkha tánon ne É:neken tiohontsá:te. Nónen entewén:ron ne owenna’shón:’a entewaién:tere’ne tsi na’tetewá:tere tánon tsi tetewá:neren nahò:ten rohsaá:nion. Tsi entewawenninéken’ne sénha ki’ ákta enkénhake ne ka’nikonhrí:io tánon ne Skén:nen.

Nahò:ten kaio’tats aionhtén:ti tsi niiohahó:ten ne tsi niiawénhseron shahón:ne kénthon ne ákte nithoné:non. Ne Skén:nen Rón:nis shonkwarí:honte tsi naetewá:iere, nek tsi onkwahrokhátshera, taetewatharón:nion tsi naetewá:iere ne thénon iah tetsoió’tens. Kí: tió:konte tetkaríhshions ne thénon ktitió:konte tsi tewakwatá:kwas tsi nónwe nitewáte aetewathárahkwe ne orihwí:io tsi niiawén:en. Do’-gah – tóka (teiontnenhsohrokhons) wathró:ris tsi teió:ken tsi sanonhtón:nions: tewaia’totáhrhon tsi na’tetiá:tere tsi tetewate’khahákhwa, iah tetsonkwahrokha’tsherá:ien, tha’tentewatnenhsó:roke tsi tentewarihwa’será:ko, ne e’tho ní:ioht aetión:ni ne aontaionkwáhnhe tsi nek tetewatahsáwha.

Do’-gah – tóka (teiontnenhsohrokhons) átste nonkwá:ti nonhsónhtati ohén:ton iasataweia’te ne tsi teshakotina’tón:ni. Tsi Iotéhrhate, tóka’ íhsehre. Iorihowá:nen kí:ken tsi ní:ioht tsi káhson iah ki’ thaesahteron’ne tsi nónwe ne shakotina’tón:nis. Nónen nà:kon íhse’s ne tsi kanénhstahere ne kanonhsésne, ken enwá:ton entewatia’taró:roke skátne tsi aetewathró:ri, aetewatahónhsatate tánon sha’taetewatste ne thénon.

Iah tha’tekaia’torétha ne ka’nikonhrí:io, karihwanón:we’s kakaén:ions tánon watahónhsatats. Ne Staats raorihwáke ne ki’ ki ne raráhstha raoio’ténhsera. Ne tsi nihaia’tó:ten, watié:sen ahonwa’nikonhraién:ta’ne, rehiarahtsherí:io ne kenna’teiá:wens tsi rotion ne raohrokhátshera. Ne 1969 ioiakén:en wathró:ris ne teioni’tón:ni tsi kawennotátie tsi tetiowennón:tie’s, shatikwatá:kwas ne kén:en tánon ne sénha ákte nitiawé:non, kahòn:tsi ní:ioht tsi kentskará:here; tsi niió:re rati’rhó:roks Ne Kahiatonhserarà:ken; tánon sénha ietsóhskats Altamont nitiawé:non tkaráhstha. Ne Staats ráton testiatié:ren tsi ní:ioht tsi ieráhstha ne Beth Bagby tho iewasón:tere ne iakehiarahstáhkhwa ne é:neken tho ní:ioht tsi skátne iá:tons ne ión:kwe (teieká:nere) rón:kwe (roterihwaién:ni). Ne ki karihwahní:rats tsi teioni’tón:ni tánon ratirihwá:ia’ks ne ktiká:te kahiatonhseróhare wathró:ris ka’niá:ien tánon óni ne aontahontka’we thénon sha’taióksteke tánon iaionhtén:ti: tará:kwi, onèn:ta, wa’kenhróntakwen… ne kéntons aiakó:tsen’te, shakoti’nikón:rare tánon aiako’nikonhraníhrha.

Ráwen ne Skén:nen Rón:nis, “Akwé:kon ne ónhka í:ienhre aiontiá:taren ne Kaianere’kó:wa iéhsehr ki’ ne Kowá:nen Karà:ken Onèn:ta aohté:ra.”

Né:ne Karà:ken Onèn:ta kará:kwen taontonte’nienténhston ne Raotitióhkwa ne tsi ne aonhá:’a karontowá:nen, ka’shátste. Tekahwishátste. À:kweks karontakén:iate réntskote ahaten’nikón:raren tánon ahathró:ri. Í:i ne karón:ta netewaia’tó:ten. Iah the teiot ne onkwa’nikón:ra tewakahrí:io tsi ní:ioht ne à:kweks. Tánon tsi teioni’tón:ni ionkwaio’tá:ti tsi ní:ioht tsi tewatoriá:nerons. Ne iah teiohsén:naien (karà:ken onèn:ta aohté:ra) ákta tsi entewakaén:ion ne ohontsá:ke ktitká:here ohté:ra teio’kenhrohétston. Tetsá:ron ki né:ne karà:ken ohté:ra ne Skén:nen, wathonkará:wis tánon sahk thíken tsi nikaié:rha. Tsi iáwe Haudenosaunee netewaia’tó:ten tewáhawe ne tahatikonhsotóntie, ne ohén:ton í:kate tsi ní:ioht tsi tewatoriá:nerons. Ne ki’ aorí:wa tewaién:tere’ ne ohóntsa ne ioronhiakentsherowá:nen ne iethisothokon’kénhen tsi iakoienawá:kon ne iah nonwénton thethoné:non. Teionkwatenhontsó:ni tahohénrehte ne rawenna’shátste À:kweks.

Tsi nientsitewe ne kanonhsésne, teiontió:ien ne “ia’taetewatehnhohawén:rate.” Ne onekóhrha kakwatá:kwen, iah teiohsén:naien (á:se tsi tekahnhoharó:ho) ne wathró:ris énska khok ónen iénsewe. Karà:ken né:ne Orihwí:io, ne ionkwahonkará:wis karontó:kon iaetewátien ne Kaianere’kó:wa ne Skén:nen. Tsi ní:ioht ne kahnhoká:ronte ne kanakerahserá:kon, kí tsi ní:ioht tsi káhson né:ne tiókonte aiakohwe’nón:ni tánon aiokwé:nion ne thénon. Ne ia’takarihwaién:ta’ne ia’tahsate’khahákwe, ahsatohétste tekahnhoharóho; íse ki nen’ ne’ ó:nen.

Tho ní:ioht tsi ionkwahtentionhátie. Ki tsi ní:ioht tsi ionkwaio’te iottakwaríhshion, aionkwaterihwaién:ni tánon aiakwatkó:rahste, í:i onkwarihwá:ke tánon ne onkwanakerahserá:kon ne Staats raorihwá:ke ne “ia’tahatehnhohawén:rate” tho nenwatókten. Ne kanonhsésne, ientewáhawe nahò:ten ki nónwa ionkwaien ákte’ nia’taionreniá’te tsi nihotiié:ren. Nahò:ten ionkwatkwé:nion tánon teionkwatewen’tawenrié:on akwé:kon thénon kéntons, tánon tsi iaonkwatahsonterátie ne kanénhstahere, nahò:ten karó:ron ne ne ohna’kénkha ktiiaonhá:’a tsi ní:ioht né:ne Ka’nikonhrí:io tánon Kaianere’kó:wa ne skén:nen, iaotahsonterá:tie iotehiarón:tie.

Skén:nen.

Martín Rodríguez: Ehécatl, comme le vent souffle dans toutes

les directions / Ehécatl, as the wind blows in all directions

February 3 - April 6, 2024

Ehécatl, as the wind blows in all directions

essay by Mariza Rosales Argonza

Once you've crossed the border, you can't really go back.

Every time I tried, I found myself "on the other side",

as if I were walking forever on a Moebius loop.

Guillermo Gomez-Peña

Martín Rodríguez's sound installation Ehécatl, as the wind blows in all directions explores the dynamic nature of mixed-race identity. The work presents a reflection on coming to an awareness of his Indigenous heritage as the wind blows across the abysses of territory and memory. It also addresses the complexity of the migratory experience, liminal spaces and the notion of territory, where narratives, temporalities, real and symbolic spaces in perpetual mutation are superimposed.

Sound is Rodríguez's principal material, and he explores modes of transmission across borders. His Chicanx imaginary, born of his cross-border upbringing in Arizona and Mexico, encourages him to explore the shifting process of identity and its relationship to territory. As Gloria Anzaldúa wrote, "Con palabras me hago piedra, pájaro, puente de serpientes arrastrando a ras del suelo todo lo que soy, todo lo que algún dia seré."[1]

In the installation, the notion of time is dislocated, and Rodríguez echoes ancestral voices and the recognition of his native heritage. He calls upon Mesoamerican mythology in the title Ehécatl, the Nahua word for the god of air and wind, often linked or assimilated to Quetzalcoatl and associated with the cardinal points of Aztec culture. The breath of Ehécatl inspires the installation's sound work, which was born from the recording of the artist childhood Eagle silbato (whistle) reverberating within an outdoor hockey rink in Tiohtià:ke/Montréal and mixed with recordings done in sites across turtle island (Rio Rico, Cuernavaca, Seattle, New York).

The recording was shared with four collaborators who have links with the artist as well as with a significant place and period in his life, so that the work moves around, opens a conversation, and brings together personal experiences. Each collaborator in turn played and simultaneously re-recorded the sound in an external location. Through these gestures of transmission, dialogue and superimposition of a recording from one person to another, the boundaries of identity and territory are diluted. Sound acts as a portal to trajectories, narratives and affects that cohabit in a dislocated time and space, inviting the public into introspective and provoking encounters, sensitive and intrinsically human experiences that resonate thanks to the artistic gesture.

The sound installation opens a timeless space, and the structure of the piece invites the public to explore the work in an investigation of meanings and frequencies by virtue of a sound spatialization composed of a constellation of five radios acting as reference points, guiding us into temporal void. These transmission channels communicate, superimpose and interact with each other, resonating with us through our bodies as we move through them, engaging us in a retrospective experience beyond time.

Like Borges' Aleph,[2] this liminal space becomes a point in space that contains all other points. Whoever peers into it can experience everything in the universe from all angles simultaneously; meaning expands and concentrates in the experience of a cosmos that unfolds within and without.

[1] Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera, The New Mestiza, Aunt Lute Books, 1999, p.70

[2] The Aleph (in Spanish: El Aleph) is the title of a collection of seventeen texts written by Jorge Luis Borges, published separately between 1944 and 1952 in various Buenos Aires periodicals. Borges' favorite themes are metaphysics, labyrinths and infinity. Translated by Roger Caillois, René L.-F. Durand, Gallimard, 1967.

Mnemonic

Dominic Lafontaine & Nicolas Renaud

November 3 - January 13, 2024

Dictionaries define the noun mnemonic (pronounced ne’monik) as “a device, such as a pattern, that assists in remembering.”

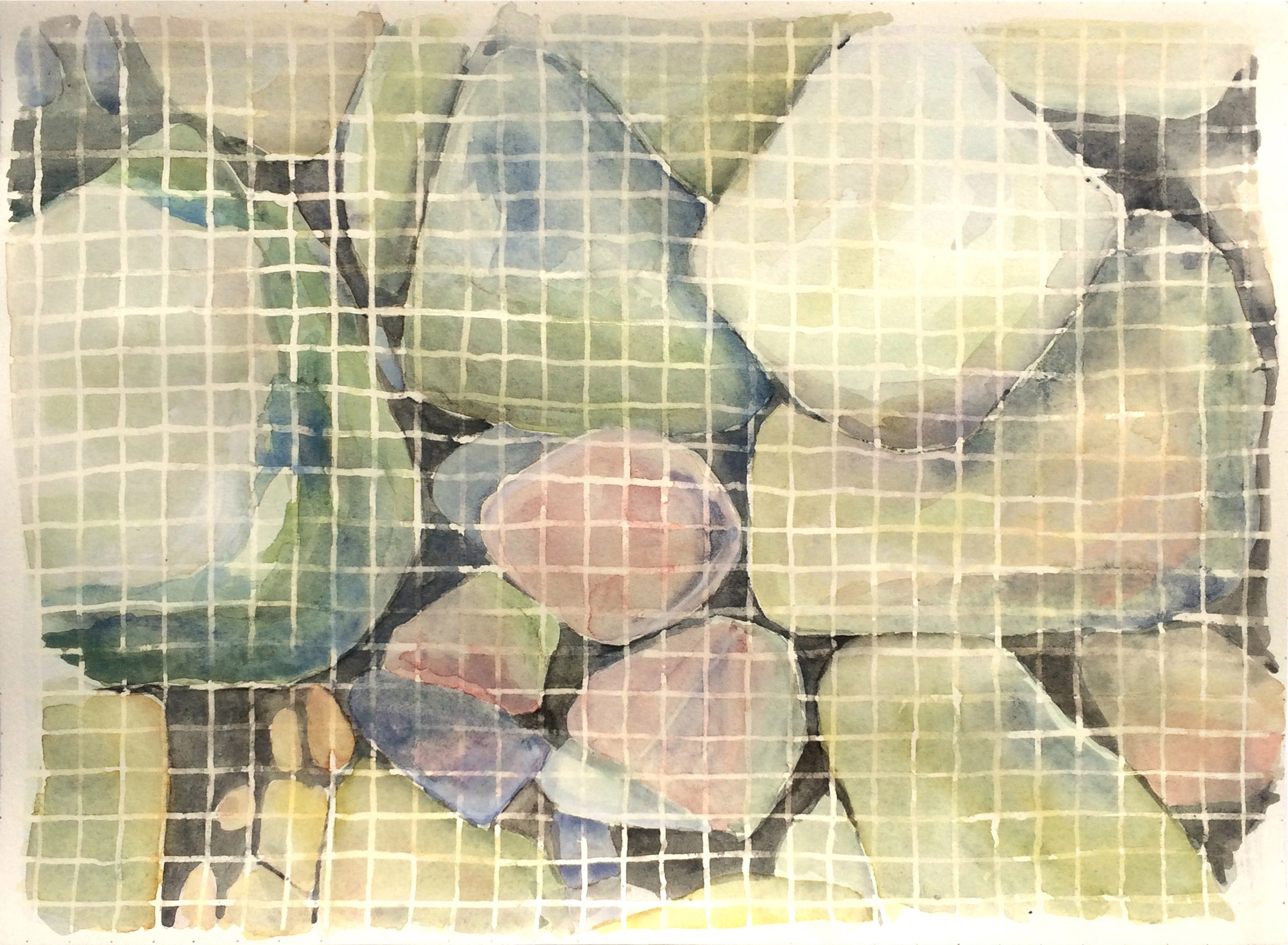

At its centre this exhibition situates wampum as a catalyst of memory, to remember history, traditions, and laws and to signify the importance of the messages associated with wampum. For Dom Lafontaine and Nicolas Renaud, the wampum is a locus from which to remember what has gone before, to think through the uses of wampum and to articulate wampum in a contemporary context and in various art media.

To begin we need to know what wampum is. The word is a shortening of wampumpeag, which is derived from the Narragansett word meaning "white strings of shell beads.” Essentially, wampum are tubular beads made from various white and purple mollusk shells. The quahog clam yields the purple beads. Various whelk species have been used to create the white wampum.[1]The white and purple beads are woven together in a tight band to make wampum belts.

In his practice, Renaud is intrigued by the hard and brittle shells as a source material. He describes these as important in the long history of aesthetic transformations of natural materials by Indigenous peoples. In this case, the shells were transitioned into objects that create meaning, carry thoughts and speech, and connect the physical and spiritual worlds. In his installation, Stained glass – screen – wampum #2, Renaud enters a dialogue with the 1678 wampum belt made by Wendat converts at the Jesuit mission of Lorette, with its prayer in Latin to “the Virgin who shall give birth.” After being troubled by the Christianized wampum belts, he came to understand this wampum as an indicator of Wendat worldview and an assertion of both identity and recognition of land and Wendat territory. He outlines Wendat agency in the historic object, and responds by bringing together wampum, references to the famous stained glass at Chartres cathedral where the 1678 wampum was sent, and the Wendat creation story. He does so through the mixing of shell beads with glass and crystal beads and the contemporary mediums, such as projection and light boxes. Similarly, Peace and war at the same time uses quahog shell beads and a mirror to highlight and reinterpret wampum as a graphic symbol. The work references the 1825 portrait of Nicolas Vincent Tsawenhohi (1769-1844), in which he holds wampum as a way to criticize broken agreements regarding the sharing of lands and waters.

Renaud uses materials often associated with traditional methods; while recognizing that working on wampum as a solitary practice is situated outside the earlier functions of these belts as markers of social, political and spiritual life. He is incorporating personal messages of identity and continuity of knowledge into his explorations with contemporary media, materials, colours, and shapes, while finding ways to still connect to the principles and language of wampum.

As an Algonquin, Dom Lafontaine sees wampum as a symbol of transaction, both political and cultural - a sort of graphic receipt. The two Algonquin belts that he knows of are interactions and agreements with Nations to the south of his territory at Timiskaming. As such they are like a modern-day hypertext that extends human memories of inherited knowledges.

As an artist Lafontaine uses the old to find the new. He uses the symbolism and the graphic materiality of the wampum to explore the relationship between native artistic practice and new technologies. He constantly searches for new media to work with and relishes the opportunity to rediscover and remix traditional materials with digital tools. He is particularly interested in knowing how Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools interpret indigenous concepts via often biased or colonial datasets.[2]

With the emergence of AI assisted art, he believes it is even more important to use archetypes and imagery to better explain and explore these new concepts of creation. His objective is to find the ghosts in the machine - in this case the ghost is AI while the mind is the Indigenous body. He seeks to see what we have in common: are we interwoven or are we separate entities?

Using Generative AI, he generates synthetic material culture as images which closely resemble human-created content. Wanna Trade Belts? is a digital art installation that explores the notion of wampum in the future. By using AI tools, Lafontaine has created wampum that bears some resemblance but pushes us forward to see and remember the belts that we have previously encountered. As the viewer we then need to invest in the generated images to see what wampum might look like in the future.

The wampum bead has always been more than just a bead. It is also a memory holding languages from the past that continue to inform the present and the future. This exhibition maintains the tradition of using a mnemonic devise to carry knowledge in the present and into the future. Lafontaine and Renaud are re-examining historic material culture to come to a new understanding, tell new stories, and explore what new and different stories will be told of Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination in the future.

[1] The purple shells come from the quahog clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) .The source of the white beads included the Channeled Whelk (Busycon canaliculatum), Knobbed Whelk (Busycon carica), Lightening Whelk (Busycon sinistrum), and Snow Whelk (Busycon Laeostomum).

[2] A data set is an organized collection of data. They are generally associated with a unique body of work and typically cover one topic at a time.

MOS

daphne partnership with 2023 MOMENTA Biennale de l’image (18th edition)Meky Ottawa

September 9- October 21

MOMENTA × daphne

Meky Ottawa

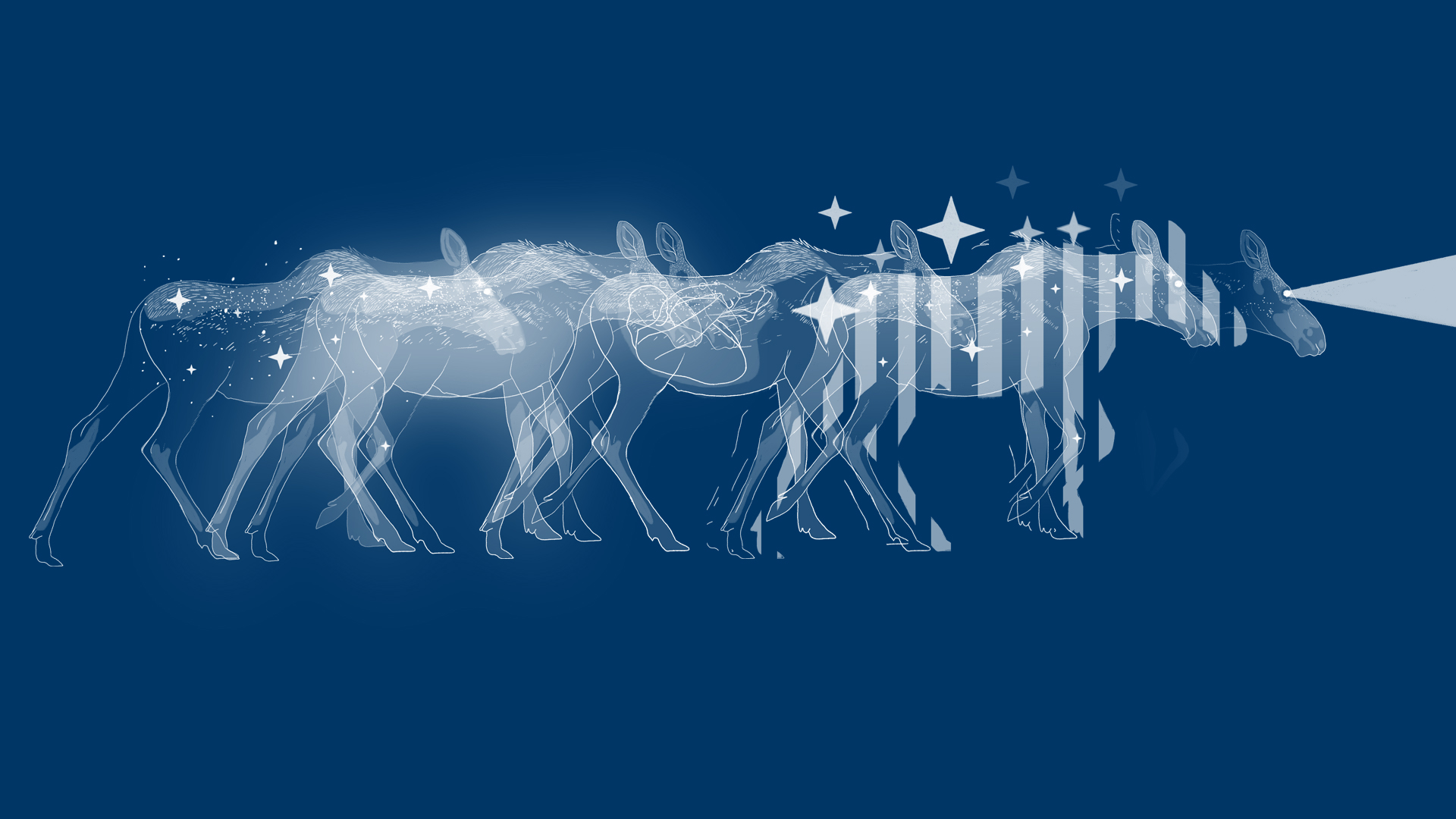

Mos

Meky Ottawa hails from the Atikamekw nation, one of eleven Indigenous nations currently residing within the provincial division of land known as Quebec. Originally from Manawan, where there is a long history of collaboration with moose, Ottawa uses this partnership as the basis and inspiration for work in a new type of material practice and experimentation. In Mos, Ottawa incorporates her flowing storytelling into work with moose leather and accessory design. She reveals the healing that comes from working with materials commonly associated with the traditional Atikamekw aesthetic while inspiring discussions about the transformative power of vestimentary choices in the context of self-determination and interpersonal identity.

In 2019, Ottawa invited audiences to “take [their] Indian Name” at the Nehirowisidigital exhibition at La Guilde.[1] The exhibition contained a high-saturation collection of digitally created labels and symbols that shared the humour of everyday life in urban Indigenous experience.[2]

In Ottawa’s practice, “Every piece starts with an idea. For me, that idea has to also come with good spirit, positive thoughts, and pride in what I am doing.”[3]This attitude that lines up well with the Atikamekw Nehirowisiw, the idea of “human beings in harmony with themselves, others, and their environment.”[4]

It is in this spirit that Ottawa invites us to take our place among the trees in Mos, where her fluid style is incorporated into a new sculptural production inspired by moose habits and habitat. From found objects and organic materials, Ottawa designs and constructs objects that are a wearable attestation to collaboration between her and her environment. It is in this way that viewers will be indulged in a unique position from which to meditate on her chosen subject.

Moose, in the Canadian pop culture imaginary, are large, dominant creatures, endangered only by the occasional hunter. However, considering the devastating fires that have been sweeping the country over the last few summers, logging and other industrial efforts that have destroyed large swathes of their natural habitat, and ongoing issues such as urban sprawl, the position of these grandiose creatures—who are known for battles that echo so loudly through the forest that treetops turn to thunderclouds—seems much more precarious. Just by taking in their near-monolithic image, though, you would never know this; as curator Ji-Yoon Han explains, “The image has a decisive role to play in ... operations of mutation, of exposure and concealment, of separation and fusion. It is an ideal tool for seeing, experiencing, and testing perceptions of the self.”[5]

Drawing on the long history of Atikamekw collaboration with the moose,[6]Ottawa uses the moose as a material through which she shapes an understanding of their relationship with the world we share and of what we can learn by observing their behaviour in response to their changing landscape. Thus, she also examines the masquerade that we, as humans, find ourselves in during times of duress and uncertainty in contemporary existence, wherein choosing how we display ourselves, our relationships, our struggles, and our successes has a truly transformative power in the context of self-determination and interpersonal identity. By doing this, she also reveals the moose as a symbol of personal healing and growth.

Ultimately, Mos is a study of contrasts that brings together textures, scale, and forms of spaces that humans and moose inhabit. These juxtapositions encourage viewers to reconsider the relationship with space that moose maintain within the context of the forest. In turn, this relationship serves as a tool through which Ottawa urges us to re-evaluate our positionalities as a species in the urban ecosystem and to question the balance of power in relation to all other objects and living beings in our environment.

Text by Katsitsanó:ron Dumoulin Bush

[1] La Guilde, “Meky Ottawa - Nehirowisidigital,” https://laguilde.com/en/blogs/expositions/meky-ottawa-nehirowisidigital.

[2] Ka’nhehsí:io Deer, “Please Take Your Indian Name: Artist Explores Beauty, Humour, and Identity Politics in Montreal Exhibition,” August 5, 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/meky-ottawa-montreal-exhibition-nehirowisidigital-1.5231961.

[3] Unpublished (at the time of writing) interview that took place between the writer and Meky Ottawa in January of 2023.

[4] Benoit Éthier, quoted in Louise Vigneault, “Actualiser les traditions, raviver la mémoire,” in Louise Vigneault, ed., Créativités autochtones actuelles au Québec (Montréal: Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 2023), 105 (our translation). In a footnote, Vigneault notes that Marthe Coocoo attributes this term to a spiritual dimension bringing together the morphemes “being in harmony, in agreement” and “identity, reputation” (our translation). See Vigneault, “Actualiser les traditions,” 105 n47.

https://www.scribd.com/read/638101870/Creativites-autochtones-actuelles-au-Quebec-Arts-visuels-et-performatifs-musique-video#

[5] Ji-Yoon Han, “2023 Theme. Masquerades: Drawn to Metamorphosis,” Momenta Biennale, 2023, https://momentabiennale.com/en/the-biennale/2023-theme/.

[6] “Rites and Traditions,” Tourisme Manawan, http://www.voyageamerindiens.com/en/discover-manawan/our-culture/rites-and-traditions.

__________________________________________________________

Celestial Bodies / Corps célestes / Enangog Bemaadzojig

daphne partnership with articule (CAM Indigenous Emerging Curator)

Dayna Danger, Duane Isaacs, Rob Fatale

curated by Jesse King

June 30 - August 13

Celestial Bodies / Corps célestes / Enangog Bemaadzojig gives a platform to three Indigenous artists who identify themselves within the LGBTQIA2S communities and as Two-Spirit &/or indigiqueer. Through the theme of ‘desire, euphoria, despair and dysphoria’, the objective of this exhibition is to question the role of colonial presence, and the ensuing, and often constricting, societal norms regarding identity.

Being Two-Spirit is to transcend the colonial structures that have forcibly surrounded identity and gender.

This exhibition opens a space for rarely heard voices.

The curatorial residency and exhibition are a daphne x articule collaboration funded by the Conseil des arts de Montréal, Indigenous Arts Residency.

Eh káti’naióhton ne onkwa’nikòn:ra /

Mì àjaye ki midonenindjiganan pejigwan /

Et maintenant nos esprits ne font qu’un /

And Now Our Minds are One And Now Our Minds are One

daphne Co-founders, Hannah Claus, Skawennati, Caroline Monnet, Nadia Myre: Inaugural Exhibitioncurated by Michelle McGeough

June 21 – August 19

And Now Our Minds are One / Et maintenant nos esprits ne font qu’un / Eh káti’naióhton ne onkwa’nikòn:ra / Mì àjaye ki midonenindjiganan pejigwan : daphne Co-founders, Hannah Claus, Skawennati, Caroline Monnet, Nadia Myre

Essay by Michelle McGeough

And Now Our Minds Are One brings together for the first time the artistic visions of the four founding members of daphne; Hannah Claus, Caroline Monnet, Nadia Myre, and Skawennati. The range of material, mediums, and artistic visions expressed in these works speak to the notion of place and our relationships and responsibilities as Indigenous people to the natural world and each other. These works celebrate and mourn these relationships. There is a recognition of shared history and lived experiences within settler colonialism, but it is not a story of victimry. These works stand as a testament to how Indigenous women are and continue to be the centre of our communities.

The Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen (Words Before All Else) is a protocol that is a reminder of the relationship human beings are meant to have with all of creation and our responsibilities to uphold these relationships with respect and humility. [1] For the Onkwehón:we, this relationship was formed when Skywoman fell from the heavens and brought this land, that we know as Turtle Island, into being. The creation of our world was accomplished through the cooperation and help of all creation. The recitation of Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen is a reminder of the obligations that we have to all living beings and a recognition that our survival is dependent upon these relationships. The words “and now our minds are one,” spoken following each greeting and acknowledgement in the protocol, is a recognition that we are a part of this covenant, and all our actions should reflect this.

Skawennati’s futuristic rendering of the Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen is spoken by the artist’s avatar xox, inKanien’kéha and the two languages of colonization: English and French. In cyberspace, new worlds are possible, as Skawennati asserts the primacy of the Kanien’kéha language, and the other languages become silent by the end of the address. Her use of a female avatar xox reminds the viewer of women’s central role in Indigenous societies before colonization and asserts women’s continued presence and power in new worlds.

Recognizing that we are on the threshold of a new world is the subject of Echo of a Near Future. Caroline Monnet’s monumental photograph presents a compelling intergenerational portrait of Indigenous women. Each woman in the image has a presence that defies a voyeuristic gaze. The regalia they wear is fashioned from construction material, suggesting a narrative that expresses an idea of home and the making of a home. The photograph speaks not only to the future but to an empowered manifestation of the present and past as the intricate laser cut designs on these futuristic garments are beadwork patterns passed down to current generations from the Anishinaabe matriarchs of Monnet’s family.

Through our matriarchs, we trace the continuous lines that connect one generation to another. Continuous lines are reinforced by the memories and stories shared; through these communal histories, the connections from one generation to another are solidified. Nadia Myre’s sculpture entitled Rita connects two Indigenous women: Myre’s grandmother, Rita, and late Algonquin artist Rita Letendre. While Myre states that this is not a homage to these two women, it is a recognition of their influence on her life and artistic practice. Rita is part of an ongoing series of works that Myre refers to as experiments in painting with clay. Based on photographs taken by Myre of sunrises and sunsets, she shares that these clay abstractions are like vessels and, as such, are capable of holding memories and desires.

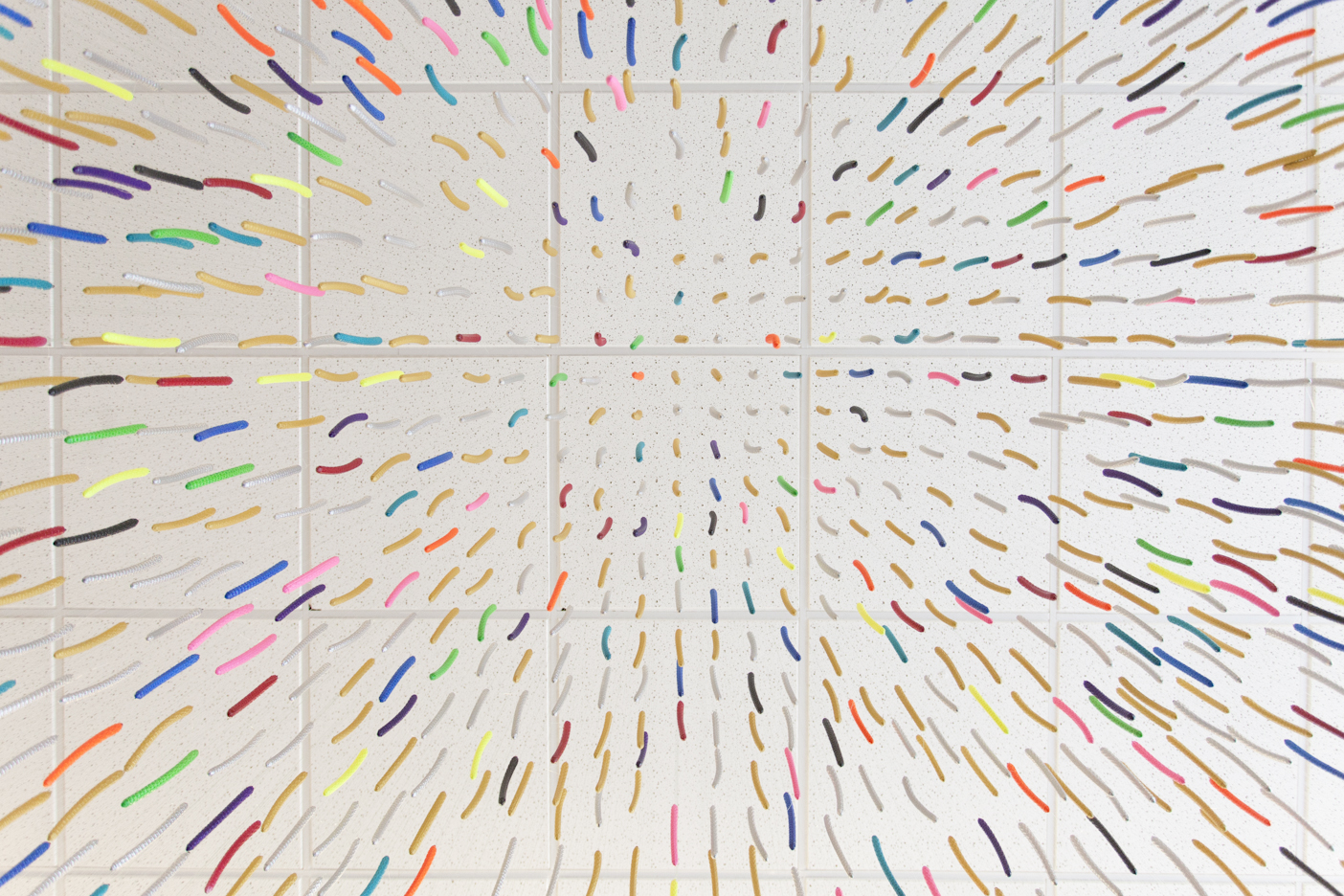

Hannah Claus’s installation teyoweratà:se (twisting winds) evokes nature’s beauty and power. Here Claus captures the energy and tension created when opposing forces converge. Claus manifests the invisible in a very tangible and powerful way, capturing the tension created by the anticipation of the moment. It is terrifyingly beautiful. While we may not understand the science, we are all too familiar with the aftermath that is left in the wake of this meteorological phenomenon. teyoweratà:se is one of the many manifestations of the air we breathe; when we enter this world, our first act is breathing in this life force, and it is our last act when we transition into the next.

The Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen reminds us of our responsibilities and place within the creation. Settler colonialism has attempted to disrupt these connections, whether our relationship with the natural world or with each other. However tenuous these connections are, we know that our survival as a people is dependent on these relationships.

[1] Words that come before all else: Environmental philosophies of the Haudenosaunee. Cornwall Island, Ont.: Native North American Travelling College, 2000, p.8.

Shii'itsüh | Pleurs dans le cœur | Crying in the Heart

Teresa Vander Meer-Chassé

May 13 - June 30, 2023

Shii’it Süh/ Crying in their heart / Pleurer dans leur cœur

Teresa Vander Meer-Chassé is a proud Niisüü member of White River First Nation from Beaver Creek, Yukon and Alaska. She currently resides on Songhees, Esquimalt and W̱SÁNEĆ Territories in Victoria, British Columbia. She is an Upper Tanana, Frisian, and French visual artist, emerging curator, and Master of Fine Arts candidate at Concordia University in Studio Arts. Her visual arts practice is invested in the awakening of sleeping materials and the reanimation of found objects that are rooted in understandings of identity.

As a way to process grief and loss, I have created a literal and metaphorical shelter that has been reclaimed, reconstructed, and revitalized. Having found myself in deep internal conflict following the loss of yet another family member to substance use, I invite you to enter Nee’ Shah | Our House to witness the importance of awakening sleeping materials as a method of navigating loss. Through the processing of natural materials with my family, I attempt to empower you to witness universal cycles of loss, grief, and mourning.

By way of patches, I translate text I have sent to family members that I have lost to or are currently experiencing substance use disorder. I do not personally experience substance use disorder; I am only a witness and a loved one to many that are experiencing or have experienced substance use disorder. Symbols, colours, and patterns that represent my Upper Tanana, Frisian, and French families and communities are present throughout the tent and act as protection, grounding, and connection. Natural materials were collected and processed collaboratively as a family and became a daily ritual in my self-growth and grief recovery.

CONTENT WARNING: This exhibition includes themes of loss, grief, and substance use. Hǫǫsǫǫ dìik’analta’ de’ (take care of yourself).

Nee’ Shah | Our House 2023

Taathǜh (Canvas Tent) - I upcycled and reclaimed a used canvas wall tent from my community of Tthèe Tsa’ Niik (Beaver Creek, Yukon). There are quite a few wall tents in and around Tthèe Tsa’ Niik but many of them are brand new and actively being used. Rumour had it that the wall tent my Grandma Nelnah Bessie John had at her Fish Camp might still be there. With permission from the family and White River First Nation, I planned to visit Fish Camp with my Dad Wilfred Chassé. Before heading out, we spoke with my Uncle Ricky Johns who told us that they had already thrown away Grandma Bessie’s tent a summer or two before but that there may still be something out there that I can use.

Grandma Bessie’s Fish Camp is located directly across from the international border marker along the Alaska Highway, separating Yukon and Alaska. When I was young, Fish Camp was accessible by foot but in recent years and with development of the highway and effects of climate change, it requires a canoe to access the site. My Dad and I loaded up a two-person canoe on his truck and he drove me there in the early morning. It was turning out to be a beautiful sunny day. We unloaded the canoe and struggled through the mud to get the canoe out on the water. It was my first time canoeing that lake and it was beautiful but shallow in areas. After digging ourselves out of the weeds, we made it to the banks of Fish Camp.

We searched but came up with nothing. I became a little worried that we wouldn’t find anything to use but sure enough, as soon as I pushed passed a fallen structure, I found an old rotten canvas on the ground. We eventually got the canvas tent in the canoe and paddled back to the highway. While we were paddling, two swans took flight beside us and it marked a wonderful moment of reclamation, family, and rediscovery. I transported the wall tent back to Victoria, British Columbia where my Mom Janet Vander Meer and I spent a week cleaning the tent to rid it of all mold and other toxins. I completed the wall tent’s reconstruction at the Ministry of Casual Living in downtown Victoria.

Ch’ithüh (Home-Tanned Hide) - Throughout my Master of Fine Arts degree, I spent the majority of my summers in Tthèe Tsa’ Niik working on a dinǐik thüh (moosehide) with my Mom Janet Vander Meer and my Grandma Marilyn John. My Mom’s partner Dwayne Broeren shot a dinǐik choh (large bull moose) in the fall of 2020. They skinned the dinǐik and left the flesh outside to freeze over the winter. During the cold months, a starving wolf entered the community looking for something to eat. The wolf ended up destroying the hide and leaving a small chunk of the rump left on the fleshing pole. I wasn’t confident enough to work on a dinǐik thüh choh to start with so the small rump piece made the most sense. However, I soon learned that many hide tanners actually remove the rump because the skin is quite thick and the shape makes it difficult to scrape.

For the first summer, I lived with my Grandma and we got as far as we could on the dinǐik thüh by way of her memories. I would ask her questions about her childhood, before she was forced to attend Lower Post Residential School. I asked her what she remembered of her Mother and Grandmother tanning hides, what she saw, what she smelled and heard. We made it quite far into the process until memory was not enough and we needed assistance. A community of young hide tanners came to our aid and offered their knowledge and skills which helped immensely. Unfortunately, on my final trip to complete the hide, we were hit with various factors that prevented me from smoking the hide properly.

Feeling somewhat of a failure and experiencing the loss of the dinǐik thüh that we had worked on over the course of two years, my Grandma Marilyn had a solution. She had been saving two ch’ithüh that her sister Nelnah Bessie John had completed before her passing in 2000. Grandma Bessie was the last person to successfully complete a hide in the community. I decided to use the hide that Grandma Bessie had already begun cutting up prior to her passing. And I am honoured and very grateful to my Grandma Marilyn for allowing me to display this piece. This is certainly not the end to our tanning journey, just the beginning.

Mēet Thüh (Lake Trout Skin) - Shnąą Thielgay eh naach'akch'įǫ. My Mom Janet Vander Meer, her partner Dwayne Broeren, and his brother Doug Broeren, took me on my first official fishing trip to Kluane Lake in the summer of 2021. It was supposed to be the annual fishing derby but because of the COVID-19 pandemic, they canceled it that year. Despite the cancellation of the organized event, numerous boats still decided to go out on the lake that day. Lake trout, white fish, and grayling are the most common fish you can find in White River First Nation Territory. My Mom and I caught a large 20-lb lake trout on that sailing, however we ate it and did not keep the skin.

I learned to tan ∤uuk thüh (fish skin) from Vancouver-based artist and tanner Janey Chang. I took a workshop with Janey online and proceeded to tan more than 40 skins while I was in Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang/Montréal for my final semester of coursework. Upon my return to Tthèe Tsa’ Niik Dwayne had saved me a ∤uuk thüh to tan that was from our Traditional Territory. I decided to tan the mēet using the oil method. I was given a recipe from Beaver Cree artist Cheryl McLean and it worked wonders. Along with my Grandma Marilyn John, my Mom, my Auntie Rosemarie Vandermeer, and my Niece and Goddaughter Sophia Vandermeer we worked on processing the mēet thüh. Four generations of hands touched this ∤uuk.

Dinǐik Tth’èe (Moose Backstrap Sinew) - My Mom Janet Vander Meer and her partner Dwayne Broeren hunted a dinǐik and butchered it on site. My Uncle David Johnny had come to help them cut the dinǐik. He told them stories and identified the dinǐik tth’èe which they cut out and kept for me. Long before I was interested in tanning a hide, I was more keen on learning how to spin sinew. I remember watching my Grandma Marilyn John do it when I was young but I wanted to try it for myself. My Grandpa Sid van der Meer mailed the dinǐik tth’èeto me and my Mom and I learned how to spin from my Grandma over speakerphone. We listened to her and told her how it looked. I took the sinew with me on another trip back home and Grandma gave me the thumbs up that I had spun it correctly.

Donjek (Silverberry Seed Beads) - My Mom Janet Vander Meer, my Grandpa Sid van der Meer and I decided to take a trip down to the White River. I wanted to collect some of the ash sediment on the banks of the River for a project. My Grandpa enjoys playing tour guide and it was an area he hadn’t explored for quite some time. He had a cabin and business along the highway near the White River. It was my Mom’s first home. The structure is now being reclaimed by the nän’ (earth). We spent the entire morning collecting ash, rocks, and driftwood along the river. As we sat to catch our breath, I noticed a bush filled with silverberries. I was gobsmacked because I didn’t know where the jik (berries) grew. I knew they had a seed inside them that was and is still used today to make beads. We collected as many as our pockets could hold and brought them back to Tthèe Tsa’ Niik to be cleaned and dried. My Grandma Marilyn John told us that you could eat these berries and that the seeds were used to make beads but that the practice wasn’t done as often today.

Nuun Ch’oh (Porcupine Quills) - I gathered these nuun ch’oh with my Mom Janet Vander Meer off a nuun that Dwayne Broeren had killed for my Uncle Patrick Johnny. My Mom and I sat in the back of her Ford F150 plucking away and smacking the nuun with a towel to gather as many quills and hair as possible. We had to move quite quickly because my Uncle Pat was eager to eat! After we gathered as many nuun ch’oh as we could, we watched as my Uncle Pat used a blow-torch to singe off the rest of the quills and fur before he skinned and gutted it. Apparently the feet are quite tasty however I didn’t indulge.

New Zealand Brown Sheep Yarn - I was gifted two New Zealand brown sheep rugs from Shuudèh Wunąą (My Sweetheart’s Mother) Rosyland Frazier. I wasn’t sure at first what I was going to do with them but in a flash decision, I decided to teach myself how to spin yarn. I picked up a few simple tools from a local yarn store and watched more online tutorials than one should. I decided to use the handspun yarn in a blanket stitch pattern in certain areas of the tent.

Melton/Stroud - Melton is a woven wool fabric that dates back to early fur trade in what-is-now-called northern Canada. Until quite recently, Canada had its own melton company however it closed and we now have to import melton (or stroud). My first dancing dress was made of red felt and I recently made my Grandma Marilyn John a tunic from white and red stroud. In the creation of Nee’ Shah | Our House, I wanted to include our family colours - red and black - with melton. I cut the melton into symbols that are representative of Upper Tanana communities. I was lucky enough to have seen some of these symbols on works by the Elders of our Elders during my visit to the McCord-Stewart Museum and the Field Museum.

Other materials include: canvas, cotton fabric, embroidery yarn, crochet yarn, nylon thread, cotton thread, polyester thread, glass seed beads, vintage seed beads, galvanized gold delica beads, ABS pipes and fittings, metal fittings, notions, rope

Tsin’įį choh (big thank you) to everyone that supported me on my learning journey. From hands-on learning to sharing memories, stories, and language, I have been blessed with numerous teachers throughout the past few years as I underwent my Master of Fine Arts degree. This journey would not have been possible without the following contributors and supports: Janet Vander Meer, Marilyn John, Wilfred Chassé, Dwayne Broeren, Sid van der Meer, Christopher Walton, Lisa Jarvis, Rosemarie Vandermeer, Tuffy Vander Meer, John Vandermeer, Jordan Vandermeer, Deuce Vandermeer, Quanah VanderMeer, Sophia Vandermeer, Patrick Johnny, David Johnny, Ricky Johns, Jolenda Benjamin, Bessie Chassé, Courtney Wheelton, Montana Prysnuk, Angela Code, Janey Chang, Cheryl McLean, Jesse Lemley, Rosyland Frazier, White River First Nation, Ministry of Casual Living, Field Museum, McCord-Stewart Museum, YVR Art Foundation, Concordia University Studio Arts Staff, Faculty, and Peers, MFA Supervisor Surabhi Ghosh, Centre d’art daphne’s Board and Staff, Lori Beavis, John Player, and to everyone that has offered an encouraging word or a helping hand - thank you.

Bebakaan

Carrie Allison, Christian Chapman, Matthew Vukson

curated by Lori Beavis

November 19, 2022 – January 28, 2023

Bebakaan / Each is Different: Carrie Allison, Christian Chapman, Matthew Vuckson

With thanks to Alan Corbiere for the Anishinaabemowin translation

Bebakaan is Nishnaabewin for ‘each is different.’ The word came about, with good help from Alan Corbiere, while processing the element/s of the works in this exhibition. I was thinking of expressive words like, ‘alternatively’ or ‘exchangeable’ because, while the artworks relate to one another through the preoccupation of bead work, they are all in some way different from one another and different or outside of our expectations of beadwork.

The 3-person exhibition, Bebakaan with Halifax-based Carrie Allison (nêhiýaw/Cree, Métis, and mixed European descent), Christian Chapman (Anishinaabe) from Fort William First Nation in northern Ontario, and Matthew Vuckson (NWT Tlicho Dene) living and working in Lac Brochet, Manitoba brings beading out of the realm of the intimate and fixed, to over-scaled, animated, and immersive. The works included are a method for each artist to discuss place, positionality, histories, and identity in their own way.

Beading is the place setter for the work in Bebakaan. Across history, the practice of beading has been widely recognized by the peoples as a means of recording and translating cultural knowledge. Christi Belcourt has written, “Beading is deeply rooted in land-based histories and relationships bound up with stories and storytelling … [as such] beading carries the stories of how cultures have adapted over time.”

The cultural belief that beading – in whatever form it takes, brings people into relationship with one another and with their own nation-specific lands, histories, identities, and worldviews is demonstrated in this exhibition.

Carrie Allison’s animated beadwork responds to her maternal ancestry as a way for her to think through connecting and reconnecting to land, both visiting and ancestral. Her work combines old and new technologies to tell stories of the land, continuance, growth, and of healing. TO HONOUR (2019) is an experimental beaded animation exploring the concept of returning beadwork back to the landscape. Miyoskamiki (2020) is a beaded animation that depicts the blooming of a Prairie Crocus, one of the first plants to emerge once winter begins to turn to spring. Customarily, hunter and farmers watched for these plants to mark the turning of the seasons. Nishotamowin (2020) is a nêhiyawin/cree word for understanding or self-in-relation. This is an audio piece that thinks through ‘getting to know’ or understanding by listening to the actions we carry out. By using contact mics and microphones while beading, Allison was able to amplify the small sounds made through the gestures of beading. The viewer connects to the audio through a QR code to tune in to the sounds that filter through the window of Allison’s studio, as well as her amplified beading gestures and spoken thoughts. Allison’s works are gestures to seek understanding and to connections to family, language, and land.

Christian Chapman creates his paintings and silkscreen prints to tell stories often using the Woodlands-style. This is a distinct style of art that blends traditional stories and contemporary mediums with bright colours and bold lines. Chapman is well-known for the insertion of easily recognizable figures – Princess Diana, Queen Elizabeth II, or Elvis onto a flat field where the figure is surrounded by florals and animal shells or hides. However, since 2017, he has been inspired by the creative community of women who make and bead their regalia. He turned to the more intricate beaded details of the regalia, he says, because both his partner and his sister, along with other women in his near and extended family are bead workers. He made the decision to paint the bead work patterns to a vastly over-scale degree, as a way to better understand the delicate glass beads and the floral patterns. At the same time Chapman continues to work within the visual heritage of the Anishinaabeg beading patterns as a method to make connections with family histories, stories, and the land on which these relationships were formed.

Tlicho Dene artist Matthew Vukson is a teacher. Teaching others is part of a continuum that he has experienced – he was taught to bead by his mother and now he teaches this skill to others. Vukson likes to share stories that have been passed on to him from his family and he enjoys talking about his beading journey. He uses art as a form of reclamation and reconciliation.

In the immersive work in this exhibition, he steps aside from the floral beading work that he was taught to turn his eye to the experience of violence and police brutality. In his work we find police badges, Police Badge 1, 2 (2019, 2020), handcuffs Cuff’em (2022) and a hangman’s noose, Calculating Weight (2022). This work that speaks of brutal responses to the Indigenous body is balanced by beaded images that centre Indigenous cosmologies as a source of healing and nurturance. In work such as Place Before Time (2019) and Orbital Station NO 2 (2021). While other work such as Red Walker (2018) and Octavial (2019) remind us of the strength that we can draw on when we return to the land to walk through forest, masses of wild flowers, or to sit and watch the Northern Lights in Place Before Time(2019).

While in this exhibition, Vukson’s work is situated most deeply in the realm of customary beading his subject matter sidesteps of our expectations of beadwork. Allison and Chapman also change up the notion of beading as the play with movement and scale. Yet all three artists are, in their own way, making plain the continuity of the tradition of beading embedded in Indigenous art, with a difference.

Versification/ Teskontewennatié:rens

Carrie Allison, January Rogers

curated by Ryan Rice

September 10, 2022 - October 29, 2022

Versification: 10 Questions

Ryan Rice: Given there are formal westernized rules and structures around writing prose that you clearly challenge in your work, can you describe or define how the exhibition title Versification represents this compilation of works being presented? Can we understand or read it as a decolonial re:action?

January Rogers: Great question. I liked and chose the title Versification because it so aptly made reference to the promotion and use of verses activated in the poetry circulating in various forms throughout the exhibition. I am using language, inviting language through words and images to speak the meaning of these pieces with open ended outcomes, whereby or through which the viewer is welcome to take and interpret from their personal interactions with each piece. There was a specific time in my life when I consciously chose to pursue poetry or rather allowed poetry to show me a route for my expressive outlets. And I did so by letting go of my visual art practice and turning my attentions and energies to writing. But then the visual work crept back in by way of media making, which is a very visual practice and I started to incorporate the poetry into video and performance. So perhaps the combining of those art forms, like throwing off the oppressive parameters of “traditional literature” could be seen as decolonial reactionary, but honestly, if the work is a decolonial reaction, then that’s a by-product of me, making the work serve my passions.

RR: Your primary creative practice as a writer is magnified through your experimentation and control of media (sound, performance, video) and is layered with references addressing social justice and biting critique of the colonial systems we experience. At what point, as a writer, did you incorporate and fold these tools (media) into your work? How did they amplify your voice?

JR: Well, I’m not sure the intention was to amplify my voice, but the practice itself amplified my joy. Through my work and experience in radio, I learned a few skills with producing sound and I took that little bundle of knowledge and ran with it, having so much fun experimenting and realizing that sound is such an ancient expression and that it is possible to produce narrative with sound alone. So again, my practices were overlapping; writing, sound, radio, performance, music, voice etc.

And yes, I make commentary with my work. I have to. It’s part of my responsibility as a Haudenosaunee Woman Artist. I have to make these markers in time, even if I’m reaching back into my cultural birthrights to bring them forward. Those pieces will represent a contemporary interpretation of our teachings and historical events. I have to represent myself as an artist and I’m getting a bit more bold in my practices to really include my own, personal story.

RR: I admire your versatility and fierceness of your creative spirit and how it isn’t restrained. What motivates you? Inspires you?

JR: Well, you’ve named it. It’s the “creative spirit” -- that spirit has been with me since childhood. And although I didn’t choose to “study” art and have the privileges of learning about those who came before me and the use of a proper art language through formal training, I did eventually come to that knowledge through doing residencies and through working alongside others in collaborations and through my own personal research and practice. So, I didn’t have to unlearn anything to get to find my voice as an artist. It was developed by adding to, not taking from. And I could never use “that language” to bullshit my way into cultivating an audience for my work, because I don’t have that language. I have poetry. I have instincts. I have that spirit that guides the work. I’m inspired by the honesty of lived experiences and I’m motivated by a real sense of responsibility to use the gifts and opportunities which I have been so very blessed (word without a lie) to befall me in my life.

RR: Do you feel a sense of urgency to “do” (as in making art)? If so, does this urgency drive your work?

JR: No.

RR: As a full-time artist (broadly defined), where do you find the energy to manage and hustle not only the literary environment, but also multiple projects that cross-over into visual culture and media.

JR: It becomes a wonderful puzzle and complex dance at times. But again, it was something I’ve done since childhood. I remember, in grade 5, writing plays and getting all my friends to act them out. They were very feminist based plays, putting the female character as lead, as hero to the story. I was raised by a feminist mother in the 70’s and 80’s. In a time when the word “feminist” was connected to the words “Women’s Liberation”, which was a different time and with a different meaning. But I was also supported as a young writer in those communities. So, I’ve always been a self-starter and I believe I’m just hard-wired to be able to manage my career, as well as be the creative I need to be. I know that’s not the case for every artist and I have, since returning home to Six Nations, lent my management skills to some of the community musicians and local events. It’s work that really feeds me. So it’s not a surprise at all that I feel quite comfortable in the role as “producer” in my own projects and in collaboration with others.

RR: In your performance work, your presence is bold, unapologetic and commands attention. At the same time, I’ve had the opportunity to witness your actions as being thoughtfully poised and balanced. How do you craft this animation? Are you conscious of audience and reaction? Is this important?

JR: Audience is not important in the development of my performance work. What’s important is that I remain in the moment, that I evoke the “spirit” of the work within me, feel it in me while in performance because that “spirit” will translate, while in performance. It’s so powerful. There is so much that can be conveyed through performance and it really excites me to discover the language that comes from my body, my movement, and the combination of actions and interactions with objects. The measure of success in performance, for me, is the stinging silence when an audience is deeply engaged because I’m so engaged in my own space, thoughts, and meditation in real time. I believe we can identify elements known to performance art. We can name them and teach them. But I think what I love so much about performance art is the same thing I love about “spoken word” in that we define it by doing it and when we keep doing it (authentically), we expand upon the definition of it. These practices, like the culture itself is a living, growing thing. It needs to morph and challenge both the viewer, but more so, the artist.

RR: What was your experience producing the visual poems in the exhibition addressing residential school legacies and the Mush Hole in particular? How do you relate to this history?

JR: First of all, the images are taken from the documented performance work my brother and collaborator Jackson 2bears and I did at the Mush Hole aka Mohawk Institute aka Six Nations Residential School in 2016. Jackson has more of a direct and known history with the Mush Hole through his paternal grandfather’s story. I have a lesser-known family history with that place, but I do know that my paternal grandparents had involvement in the Anglican churches on Six Nations, which of course took them away from Haudenosaunee cultural traditions and practices. So there was a clear disruption from that generation, if not further back. The poems which live with the images are new(er), written while on a trip to Venice Italy in April 2022, which was a very challenging trip for me in many ways. But it served as a time where much self-reflection was done and I wrote several poems on that trip. Some of which I included on the Mush Hole images. This is where I tell my story. The shame of growing up visibly Native, the loss of my Sister - the only other person in the world who shared my story, the undeniable negative effects that residential school has on my reality today. I survived. I am thriving. I am celebrating 31 years of sobriety this year. Going back into that institute with images of my family, was very transformative. Through that performance work, I was able to change my relationship with that place by being mindful of my presence there as well as the presence of the spirits of those who passed through there. Their energy is palpable. I can feel them listening when I speak to them.

RR: Being from Six Nations, what is your relationship to Pauline Johnson? Do you see any parallels with your own trajectory as a Haudenosaunee writer and performer?

JR: Short answer; Yes. Long answer is I believe she came into her own as a writer and performer out of a need to express herself, out of a love for theatrics, out of a desire to stay free and a natural want to be her own person. I operate from a similar foundation as an artist and also a Haudenosaunee woman. The whole not-having-kids thing can sometimes make you seem like an anomaly in Indian Country. And Pauline didn’t have children (although there are rumours…). And I don’t see that as a sacrifice to my career. I value my freedom very very much and there’s little else I see that this world can offer that is more attractive to me than that. As a performer, what I share with Pauline is the way we’ve both taught ourselves how to do this thing called performance poetry. Other than the theatre performers, Pauline Johnson admired and there wasn’t anyone doing what she did in her time. And it’s been the same with me. When I decided to move my work into a performance poetry practice, it was all self-developed and thank goodness most of it worked. So there’s an innovative nature we share, a strong pro-female and very pro-Native agenda from where our poetry is inspired from and of course the love and need to travel to advance our careers.

RR: An “orator” has a significant role in Haudenosaunee culture, do you feel you are moving forward this tradition with your own practice? How important is it to tell, and be heard? How important is it to listen?

JR: Another great question Ryan. You witnessed the performance art piece I did with radios and if you recall in my talk post-performance, I shared, I believe we are all like radios. That is to say we have the ability to transmit (send signals) and receive. So again, I’m making reference to our energies. As a poet who speaks her words, rather than reads them, although I also sometimes read them too, I believe that how we (Native authors) participate in “literature” is but a stepping stone to bring us back to the original practice of oratory. There are many roles in our current societies which employ “oratory” in their pursuits such as lawyers, comedians, teachers, Longhouse speakers, politicians etc. So the act of “speaking” never really went away. The whole reason I started doing spoken word was so my words could be heard - not me - my words. I wanted to honour them by giving them the best chance possible of being heard. And over time, after my nerves calmed down, because there is a fear of losing the words in mid-speech, I began to present with a natural sense of stage presence and gestures. I started to have fun with it.

RR: Thinking about the tangible objects you create and the materials you incorporate and produce for your performance and media work such as costumes, props, cornhusk dolls, stepping stones, rolled cigarettes etc., all become artistic / creative representations that embody your presence that remain active as traces of your absence. For Versification, and your performance and collaborative work with Jackson 2Bears (Kanien'kehaka multimedia installation/ performance artist and cultural theorist from Six Nations), how does the remnants exhibited embody the essence of your performance?

JR: I would say through performance, we not only create experience and memory but evidence of our presence through the objects left behind. In the case of the Spirit Shadow performance, as part of the Versification exhibit, Jackson 2bears and I literally leave outlines of ourselves there in the gallery. We create negative space in the shape of ourselves, distinguished by the medicines we use in a protection ceremony, believing that the methods and actions we evoke to protect ourselves in performance, is so evident, that even in our absence, we remain....protected.

Nikotwaso

Catherine Boivin

curated by Jessie Ray Short

July 9 - August 27, 2022

In the round – Catherine Boivin by Jessie Ray Short (revised October 2023)

Catherine Boivin’s work centres on happenings that affect her personally, as an Atikamekw woman and mother living in an Indigenous community in contemporary Quebec. I listen carefully during our video chats as Catherine tells me about the concepts behind her piece, entitled Nikotwaso. Her baby daughter plays in the background of our meetings or climbs around on Catherine’s lap. Our discussions circle around a variety of topics, including current film and television interests, video art, cultural knowledge from our respective Indigenous communities, the importance of language and teaching Indigenous languages to future generations, and the ongoing gendered violence perpetrated against Indigenous women across Canada.

Catherine remarks how she now feels a weight of responsibility to address these issues, to keep her language and culture alive for her daughter. To keep her daughter alive for her culture and language. These concerns have been and continue to be voiced by Indigenous people. It can be stated that in this country, “a national narrative [has been created and] is based on Indigenous genocide… For far too long there has been an interest in Indigenous cultures but not Indigenous people or their well-being.”[1] There is no culture without the people from whom it stems. For a young woman like Boivin, the issue of murdered and missing Indigenous women is one that continues to haunt her, as is the case for Indigenous peoples nationwide (and no less so in Quebec).[2]