CURRENT & UPCOMING EXHIBITIONs

Current Exhibitions:

January 7 - April 18 2026

gallery 1:

Emma Hassencahl-Perley : Tsík nón:we iekáhson / everywhere and completely

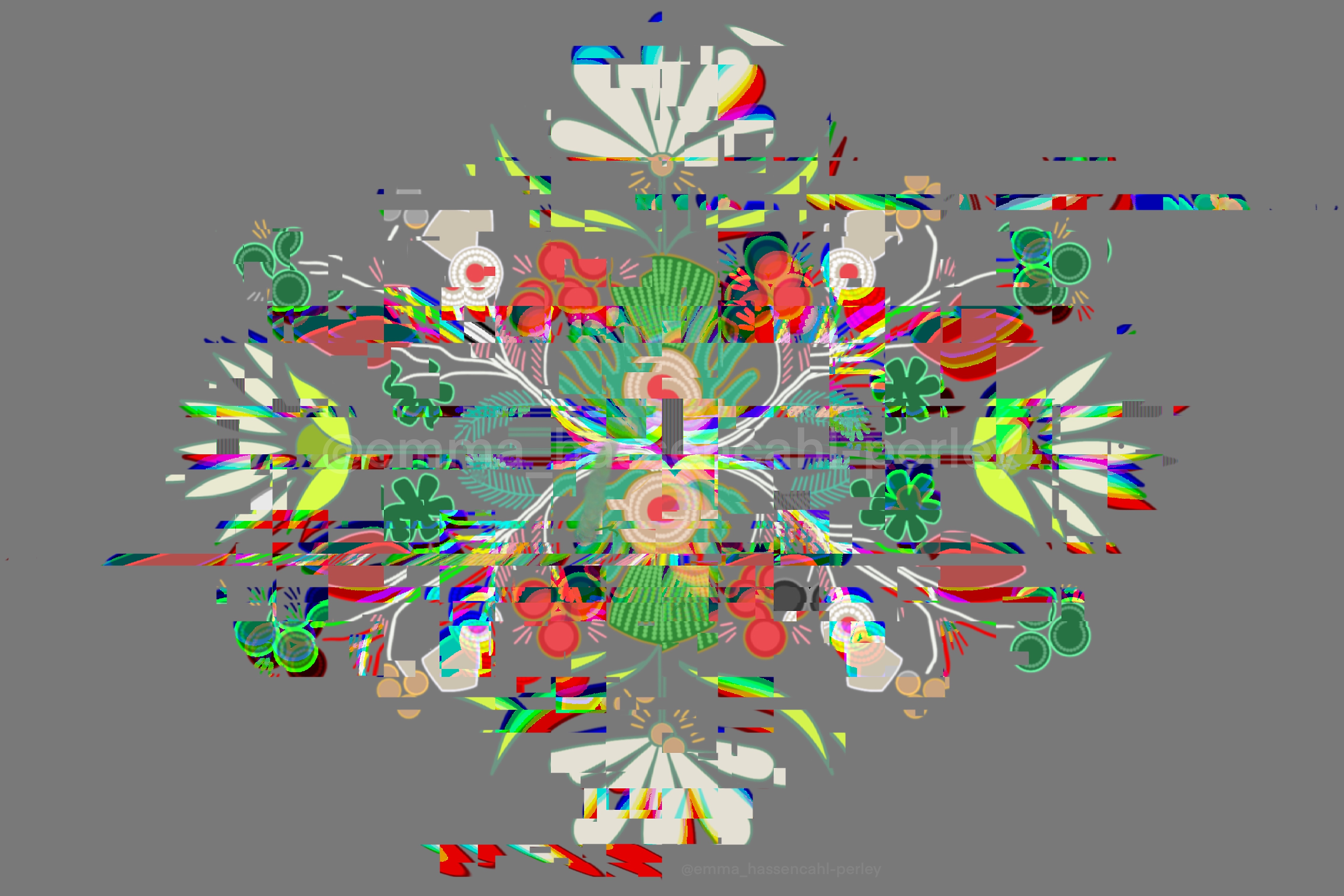

A star, a glitch, a becoming

by rudi aker

In everywhere and completely, Emma Hassencahl-Perley undertakes an intentional recalibration, moving toward the restorative call of a self-determined artistic practice – a return to a creative center – while remaining engaged in her public and communal work as an accomplished muralist. From this balance between personal exploration and collective practice emerges a mode of making as relation, as orientation, as constellation – a delicate weaving of thought and gesture. Across a decade of work, this evolving lineage traces Emma’s engagement with mediating material and digital worlds, mapping networks of memory, and exploring the shifting terrains of nationhood, activism, and cultural sovereignty.

Guided by cultural practice, language, and relationality, the exhibition title draws from the Wolastoqey translation of possesom, meaning star: pos, everywhere; sesom, completely. This interplay situates Emma and her works within expansive, interconnected worlds, reflecting how stories, relationships, and communities stretch across time and extend across generations and geographies. Constellation is both methodology and metaphor. Through these stars, networks, and fragments, Emma engages with glitches, scattering images and words to unmake, create, and recreate. These disruptions serve as reminders of the pasts, presents, and futures that have and continue to hold us, enacted through the ongoing process of coming together to ensure our survivance and possibility.

Central to everywhere and completely is Emma’s new body of paintings, where digital experimentation and material practice converge. These works arise from glitched digital drawings that are projected, traced, and hand-painted. The painterly intervention produces surfaces that shimmer between clarity and distortion. Her aesthetic language, deeply informed by Wabanaki material and visual culture, is threaded with the double-curve motif, carrying ancestral knowledge into the future through contemporary digital storytelling, bridging memory, cultural inheritance, and innovation. In these paintings, the physical and digital, the de/colonial, and the traditional and contemporary intersect to explore relational and temporal multiplicities. Rather than emphasizing the loss or erosion inherent in digital processes, the works focus on transformation – how something altered can reveal new paths of meaning, despite their distortions; they refract rather than erase.

Through the lens of constellating, the glitch functions not merely as a visual strategy but as a conceptual framework. By fracturing, displacing, and reconfiguring, Emma unsettles fixed narratives, opening space to question and reimagine histories, memory, and cultural knowledge. This practice highlights how information, histories, and culture circulate across material and conceptual spaces, shaping networks that are never fixed but constantly evolving. It enacts Indigenous epistemologies that emphasize ethical, relational, and political responsibility, showing how making and remaking are inseparable from the work of remembrance, resistance, and cultural continuity.

Anchored in a lineage of care, Emma’s work is deeply interwoven with that of her grandmothers, elders, and the larger community of Neqotkuk (Tobique First Nation), whose teachings and activism form a steady undercurrent for her practice. This intergenerational thread is evident in two of the earlier works in the exhibition: White Flag (2015) and Ahtolimiye (She Keeps Praying) (2018), both of which incorporate shredded fragments of the Indian Act, embedding colonial documentation into the material as a means of unmaking, transforming, and reclaiming. The flag asks how symbols might be remade and how nationhood might be reconsidered, while the jingle dress, inspired by her great-grandmother Marjorie Perley’s ribbon dress, embodies resilience and the vitality of Wolastoqey cultural practice. From witnessing the activism of her matriarchs, Emma learned the rhythms of movement-building, grounded in persistence, care, and dialogue. In these works, her elders’ teachings persist, adapting across material and temporal landscapes to shape Emma’s practice as a continuum of cultural knowledge and intergenerational guidance.

Throughout the exhibition, friction and transformation act as generative forces. Digital and material, past and present, intersect to show how care, memory, and knowledge flows through interconnected networks. The works reflect both the possibilities and limitations of digital spaces, recognizing that online environments carry their own forms of cultural transmission, activism, and community building. Glitches and constellations serve as reminders that knowledge, culture, and activism are never fixed, they are continuously mediated, reassembled, and renewed, in a perpetual state of becoming. In fostering dialogue between this new body of work and earlier pieces, Emma Hassencahl-Perley embraces creation as a relational, iterative, and expansive act. everywhere and completely is a field of possibility and a vision of connection that expands in every direction – reminding us that transformation, like a constellation, is always forming, gently, everywhere, completely.

gallery 2:

Jobena Petonoquot: Ni Mikawenindjgan Inàkonigewin / My Souvenir Ceremony

Our Plastic Sisters

by Sherry Farrell Racette

More than a decade ago, I taught a class on Indigenous representation in museums and public spaces at Concordia University. We used artist Jeffrey Thomas’ seminal project, “Scouting for Indians”, as a strategy to explore how these critical issues impacted us as urban citizens.[1] We divided Montreal into sections, and each student began to scout for Indigenous representation. Jobena Petonoquot was a student in that class – she tackled Old Montreal. She reported on tacky souvenir shops, and brought a little doll dressed in “Indian” clothing to class. Jobena rescued the doll, and every Indigenous woman in the class related to her impulse to care for it.

Jobena’s visceral connection to souvenir dolls is rooted in the experience of being photographed as a living doll for a government poster in the 1980s. She was four years old, posed in a fringed dress, leather headband and turkey feather. The child became the doll. Souvenir dolls are a conundrum. Their stereotypical representations are perceived as authentic. They represent real people in damaging ways and impact public perception. Misrepresentation is toxic, but we feel sorry for our plastic sisters with their pursed lips and ridiculous clothing.

The impulse to rehabilitate and deploy the narrative power of dolls is shared by several Indigenous women artists. Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith made paper dolls. Skawennati has contemplated the unlikely pairing of Barbie Dolls and corn husk dolls.[2] Australian artist Destiny Deacon rescued a vast collection of highly problematic black dolls that she reframed and reanimated through photography.[3] In the case of My Souvenir Ceremony, an Algonquin-Anishnaabekwe artist prepares the dolls for burial, blesses and transforms them. She is a remedial presence who manipulates history and rearranges relations of power.

For a number of years, Jobena has explored the overlapping spaces between personal experience, history, and colonialism with a focus on the vulnerable bodies of children. Bonnets, clothing, and moccasins are recurring forms. She has crafted a visual vocabulary, a uniquely personal system of meaning that reaches into the complexities of Algonquin history, critiquing our centuries-long relationship with Catholicism, while holding up our resilience and deep knowledge of land, birds and animals. She draws from a wide range of materials, each carefully chosen for its narrative potential. Every choice is intentional: velvet, beads, lace, hide, furs, cheap plastic, and earth from her home community of Kitigan Zibi. Every stitch is an intervention. The soles of the funeral moccasins have different images: a doll and a dead chickadee. The memorial photograph is trimmed with healing cedar. At the foot of a casket, two beavers contemplate a cross. Curves emulate the undulating trim on birchbark baskets.

As a final step in the ceremony, Jobena dressed in the same garments she sewed for the dolls: a skirt, a bonnet trimmed with lace and muskrat fur, and a beaded collar. Unlike the funeral moccasins, on Jobena’s regalia the chickadees are alive, both a symbol of persistence and a reference to her mother’s home. In a series of staged photographs, the living doll walks the streets of Montreal, returns to the souvenir store and contemplates rows and rows of souvenir dolls. She bids them farewell, kneels at a church altar and offers a prayer. When she returns, her bonnet and collar are laid to rest among the dolls, who are carefully placed on fur. The Ceremony is done with love and gentle determination to restore balance. But the message is clear. Their time is over. RIP Our Plastic Sisters.

[1] Haudenosaunee artist Jeffery Thomas’ “Scouting for Indians’ (1992-2000) was a photo-documentation project based on “scouting” for representations of Indigenous people in urban spaces. It included statues, architectural elements, street signs, and graffiti. See Jeff Thomas, “Scouting for Indians”, https://jeff-thomas.ca/2014/04/ scouting-for-indians/.

[2] Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith, Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World (With Ensembles Contributed by the U.S. Government), 1991, Obj. No. 46.2023, Museum of Modern Art; Skawennati, “Generations of Play”, https://skawennati.com/projects/generations-of-play/.

[3] Stephanie Convery, “Destiny Deacon on humour in art, racism, 'Koori kitsch' and why dolls are better than people”, The Guardian, 23 November 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/nov/24/destiny-deacon-on-humour-in-art-racism-koori-kitsch-and-why-dolls-are-better-than-people.